j'y suis jamais allée

More eventually.

weblog for http://www.ohbara.com

(silk thread and shibori button clips for my short hair from Megan)

(silk thread and shibori button clips for my short hair from Megan) (beautiful wool-and-kimono-fabric scarf from Blair, for French winters--a bit of home)

(beautiful wool-and-kimono-fabric scarf from Blair, for French winters--a bit of home) (speaking of coats and coats, I am wearing my dad's mom's nursing cape with this outfit),

(speaking of coats and coats, I am wearing my dad's mom's nursing cape with this outfit),

Because here it is fall, the season of back-to-school and cooling temperatures, and the smell of apples. And the lonely season (of mists and mellow fruitfulness! name that poet!), which makes having some invisible lines out there to you just a bit nicer.

Because here it is fall, the season of back-to-school and cooling temperatures, and the smell of apples. And the lonely season (of mists and mellow fruitfulness! name that poet!), which makes having some invisible lines out there to you just a bit nicer.

'fancy' quilt from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Makes me wish I had the patience for things like quilting and applique. From the early 1800s, but so fresh to me: the colors, the symbols. I want to make a skirt that does what this quilt does in terms of spring.

'fancy' quilt from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Makes me wish I had the patience for things like quilting and applique. From the early 1800s, but so fresh to me: the colors, the symbols. I want to make a skirt that does what this quilt does in terms of spring. mikan bracelet by Bellaceti: I've loved this bracelet since I first saw it, lo these 365 days+ ago. I love that it's called 'mikan,' I love the orange beads that actually LOOK like mandarin oranges, I love the styling of this photo. Actually, I love everything on this site, including the Lupe earrings, which I just bought.

mikan bracelet by Bellaceti: I've loved this bracelet since I first saw it, lo these 365 days+ ago. I love that it's called 'mikan,' I love the orange beads that actually LOOK like mandarin oranges, I love the styling of this photo. Actually, I love everything on this site, including the Lupe earrings, which I just bought. Brian saying my new haircut is "jolie."

Brian saying my new haircut is "jolie."  Anishinaabe bandolier bags from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: I don't think I even need to qualify this. Except maybe to say that these are beaded? With tiny glass seed beads? Yes. Amazing.

Anishinaabe bandolier bags from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: I don't think I even need to qualify this. Except maybe to say that these are beaded? With tiny glass seed beads? Yes. Amazing. Jupon from Modern Child: I love this skirt. I love the ruffle, the ruching via drawstrings, the colors, the (what I imagine to be) French quality of it. I'm working on one like it for me (don't laugh! I do NOT look like a milkmaid in it!) in yellow and grey. I just need a fabric for the outer ruffle still. My fall style is so exactly to my tastes this year--I mean, I really feel at home in it, and maybe that's because I've made/I am making so much of it. More to come on this soon--just need to find time and someone to take photos. LOTS of ideas!

Jupon from Modern Child: I love this skirt. I love the ruffle, the ruching via drawstrings, the colors, the (what I imagine to be) French quality of it. I'm working on one like it for me (don't laugh! I do NOT look like a milkmaid in it!) in yellow and grey. I just need a fabric for the outer ruffle still. My fall style is so exactly to my tastes this year--I mean, I really feel at home in it, and maybe that's because I've made/I am making so much of it. More to come on this soon--just need to find time and someone to take photos. LOTS of ideas! shop at Red Dragonfly Press

shop at Red Dragonfly Press Just tiny bits (I really use up my fabric, so when I think of scraps, I mean tiny pieces for quilting or zakkaing!) all bundled together. It was late last night when I finished, so the light in the photo is poor.

Just tiny bits (I really use up my fabric, so when I think of scraps, I mean tiny pieces for quilting or zakkaing!) all bundled together. It was late last night when I finished, so the light in the photo is poor. Or maybe a big one: everything in my shop is half off (yes, 50%!) for this week. I will be closing up shop as I move to France, so 9/21 will be your last chance for delightful bara goodies! (I'll reopen, but exactly when and in what capactiy remains to be seen.)

Or maybe a big one: everything in my shop is half off (yes, 50%!) for this week. I will be closing up shop as I move to France, so 9/21 will be your last chance for delightful bara goodies! (I'll reopen, but exactly when and in what capactiy remains to be seen.) Lisa S. asked whether simplicity has to do with it. I think it does: simplicity, and clarity, and precision, and grace.

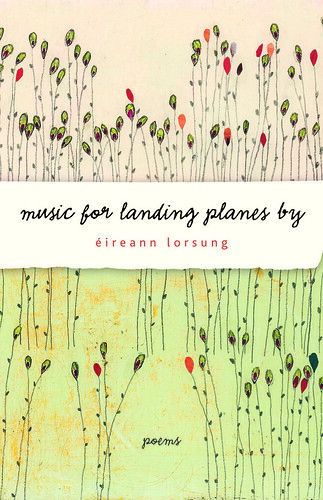

Lisa S. asked whether simplicity has to do with it. I think it does: simplicity, and clarity, and precision, and grace. I got a card from the University of Iowa press when I was a senior in college. It is bright green with bright blue writing; it reads POETRY IS FOR EVERYBODY. I hung it over my desk when I began graduate school.

I got a card from the University of Iowa press when I was a senior in college. It is bright green with bright blue writing; it reads POETRY IS FOR EVERYBODY. I hung it over my desk when I began graduate school. For me, a strong poem is marked by its innovative and intelligent use of language first of all. I am thinking of Anne Carson's writing (specifically Autobiography of Red: "Herakles lies like a piece of torn silk in the heat of the blue saying/ Geryon, please. The break in his voice/ Made Geryon think for some reason of going into a barn/ first thing in the morning/ when sunlight strikes a bale of raw hay still wet from the night"--pg. 54). The images are precise and beautiful and evocative, and they are communicated by language that is unexpected and interesting.

For me, a strong poem is marked by its innovative and intelligent use of language first of all. I am thinking of Anne Carson's writing (specifically Autobiography of Red: "Herakles lies like a piece of torn silk in the heat of the blue saying/ Geryon, please. The break in his voice/ Made Geryon think for some reason of going into a barn/ first thing in the morning/ when sunlight strikes a bale of raw hay still wet from the night"--pg. 54). The images are precise and beautiful and evocative, and they are communicated by language that is unexpected and interesting. AND A FEW QUICK TIDBITS:

AND A FEW QUICK TIDBITS:

I'll bring fabric, too. Just a few favorite things. I'm still trying to use most of it up--making things for the shops and for myself. And for friends, too. But the fact remains (more than facts alone remain, alas, or I would have MUCH less packing to do) that there are beads and ribbons and fancy Japanese papers and fabric and stuffing and bits and bobbins that I won't take with me. That maybe I would never use? And maybe you would?

I'll bring fabric, too. Just a few favorite things. I'm still trying to use most of it up--making things for the shops and for myself. And for friends, too. But the fact remains (more than facts alone remain, alas, or I would have MUCH less packing to do) that there are beads and ribbons and fancy Japanese papers and fabric and stuffing and bits and bobbins that I won't take with me. That maybe I would never use? And maybe you would?